Oscar Rabin’s Parable : Depicting reality

The atmosphere of the fifties was charged with initiatives for manifestations, socio-cultural revisions and the ideas for individualism and openness. Within circle of relatives and friends, the artists of Lianozovo found their own art critics, lovers and connoisseurs. By helping each other to develop self-sustainability, the unofficial art group took their first steps in presenting their underground art to the public. It was through Oscar Rabin, the leader of the Lianozovo “school” that a number of non-conformist artists found their way to expose their artworks to the world. Rabin’s initiative was adopted by his circle whose main goal became to present their underground art to the public and thus symbolize the self-liberation of art. Oscar Rabin was to achieve his freedom by depicting the ‘true’ reality. But what makes his works real and how does he define reality? Canvases full of objects from the byt: dark and heavy skies, the rotten smell of decay, overwhelming gravity, dramatic expressionism, ghostliness … and the Суровая реальность. It is this portrayal of ‘reality’, which gained Rabin’s artistic freedom and took away his citizenship in June, 1978.

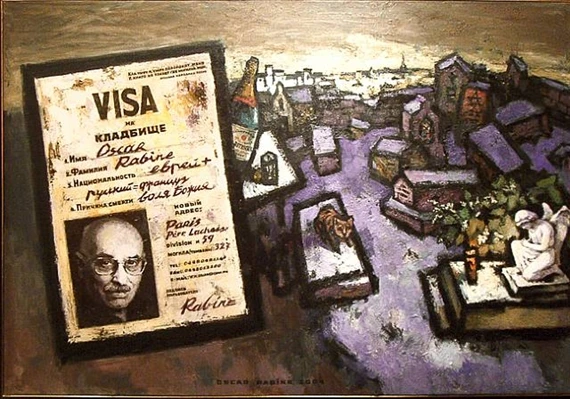

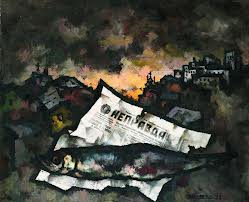

In his secret manifesto, regarding what is socialist realism, Andrei Sinyavsky-Terts declared; “… Let the exaggerated images teach us through absurd fantasy how to be truthful.” It is the same absurd fantasy, painted with thick impasto of heavy dark colors and gloomy splash of light, which Rabin has articulated to the viewer as his own reality. Through works like: Натюрморт с рыбой и газетой “Правда”(1968), Социалистический город (Город под Луной,1959) and Паспорт, (1964), Rabin creates his personal grammar of symbolic objects, which function to relate a parable in a language that screams for freedom. It is a language that goes beyond the depiction of an object, but it is rather a lyrical way of describing the mood and the feel of the domestic atmosphere. They are expressions of internal battle: an external expression of an internal discomfort. Thus, Rabin’s canvases present scenes of children-like drawings of geometrically distorted objects. Used to the direct object-representation in the socialist realism artworks, one starts to wonder: Is this reality? What constitutes Rabin’s “realism”? What does he define it as?

Rabin constructs a new reality by going beyond the objective. It is the painterly expressiveness of the object, not the object itself, which is important to the message of the artist. His goal is to depict the space, the dirt and the suffocating feel of the byt. Thus, he depicts dirt with dirty palette; he depicts the heavy skies by applying gravity with his heavy brushstrokes. The artwork is all about the sensation and the implied symbolic parable. Furthermore, he looks for a deeper, symbolic meaning in the everyday objects that he depicts. His reality is constituted of the feel of objects from his and the collective byt (vodka, fish, forks, newspapers, oranges), which he turns into symbols, whose connotation constitutes a grotesque fantasy and an ironic atmosphere. So, Rabin relates reality through the senses, not through the objective. He depicts it through a deeply individual expression of his vision and perception of the world around him. And what constitutes reality for Rabin is the experience of the symbolic objects from his byt, which nevertheless relate to a collective experience of his whole generation. Thus, he presents a symbolic reality through the experience of a whole population. His objects store a collective meaning and experience, and function as a sign of a collective consciousness. “The ideology chain stretches from individual consciousness to individual consciousness connecting them together. Signs emerge only in the process of interaction between one individual consciousness and another.”[1]

At the same time, these collective symbols raise further problems and questions to the viewer. Focusing on the paintings: Dustbin, Barracks, Натюрморт с рыбой и газетой “Правда” and Паспорт, Yevgeny Barabanov implies, “the bottle of vodka raises a questions of the country’s fate, a passport – a question of fate of an individual, a hut …a question of faith’s fate.”[2] Rabin here presents the object-symbols as problematic – ironic signs of the Суровая реальность. It is the other side of реальность that Rabin wants to portray, the grotesque реальность of the gray communist byt. In his rather ironic depictions of objects, Rabin wants to achieve a sense of freedom and express the liberalization of art itself. He portrays art as a media of liberty, where one can include the existence of foreign press, to ironically defame the portrait of Lenin and hopefully open the eyes to the blinded nation. Thus, Rabin’s canvases represent his existence outside of the homogenously gray masses; he looks at these melancholic scenes with the freedom of a bird’s eye.

On the other hand, his reality lacks the presence of human beings. Looking at his Социалистический город (Город под Луной), the ghostliness, the sense of abandonment and the dark loneliness of the streets makes one shiver. One feels empty and left alone with the melancholic moon on the horizon that is gleaming over the gray soviet blocs. The gray blocs seem to bend with the force of the wind. Their depiction in gray makes them appear dead, but at the same time they are alive with the traces of human existence. A beam of light is shining in a lonely room in the midst of dead silence. It symbolizes the existence of man. It sends us the feeling of life that is however not directly depicted … it is felt. In this manner, Rabin’s works depict existence by not directly addressing it. He makes us feel rather than observe and thus, alters our visionary processes.

Through the depiction of feeling and portrayal of objects-symbols in this way, Oscar Rabin renews the language of painting and tries to also renew the visionary process of the viewer. One is not to observe but to feel the experience of the paint. One is to perceive the world in his paintings through the experience of estrangement – to go away from the automatism of vision, to strive away from habituation of the senses. His artworks advocate the change in one’s perception and view of the world. Yevgeny Barabanov suggests that Rabin struggles to recreate the lost reality and the lost art of painting. [3] He tries to communicate to the viewer through a symbolic language imparted in his depiction of byt. I believe that, it is almost like Rabin is trying to talk to the masses in a code language. One might say that here Rabin also works out Victor Shklovsky’s theory that “art is thinking in images” and this imagery equals symbolism. The role of art, as Rabin depicts it, is to impart sensation of things as how they are perceived and not how they are known – to make objects unfamiliar. In this way, Rabin doesn’t only try to communicate in code language to the public but to also change its perception of art. His ultimate goal is: by changing how the masses look at art, they will also change their perception of the world. They will no longer rely on their habituated perception; the masses will see the real world anew with their un-blinded eyes.

Through his artworks, Oscar Rabin has opened Pandora’s Box. Skeptics may say that he has polluted and disgraced the Soviet reality. On the other hand, Rabin’s canvases have introduced a change within the grayness and an alternation of the visual perceptions. His paintings are like a symbolic parables constructed around the images of one’s byt.

References:

Barabanov, Yevgeny. “Vision and Recognition.” (2007): 9-10.

Voloshinov, V. “The Study of Ideologies and Philosophy of Language.” Tekstura (1993): 4.

Citation of Artworks

1. Оскар Рабин. Социалистическийгород (Город под Луной). 1959.

2. Оскар Рабин. Паспорт. 1964.

3. Оскар Рабин. Помойка № 8. 1970.

5. Оскар Рабин. “Натюрморт с рыбой и газетой “Правда”. 1968 г.

[1] V.N. Voloshinov, “The Study of Ideologies and Philosophy of Language,” (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 4.

[2] Yevgeny, Barabanov, “Vision and Recognition,” (St. Petersburg : Palace Editions, 2007), 10.

[3] Ibid. 9.